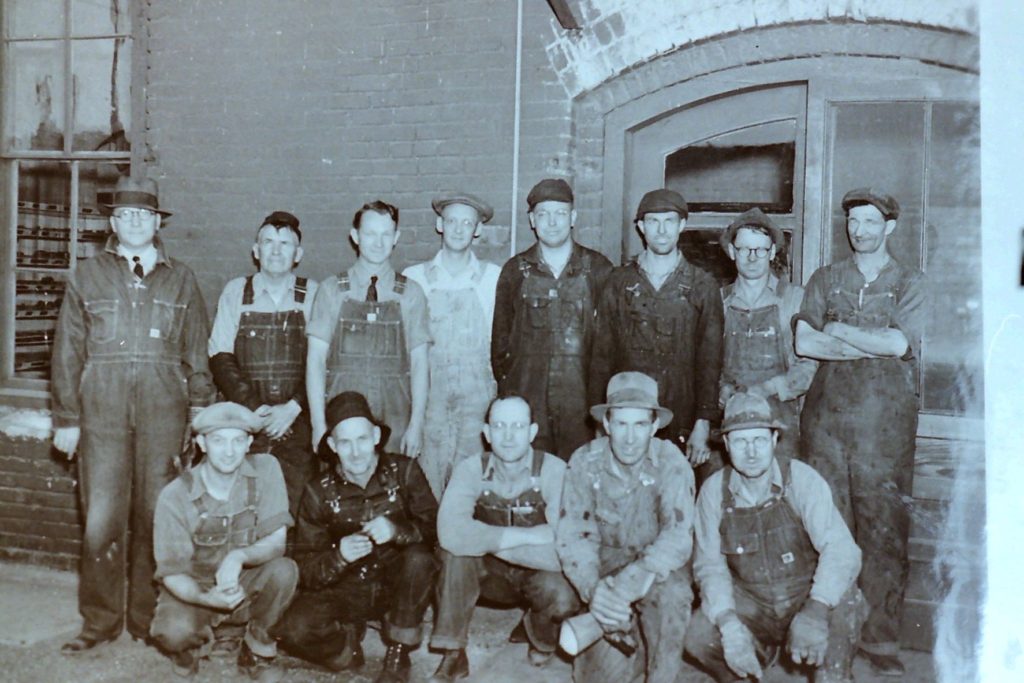

The following is a “tale” from the memoirs of Earl Trousdale titled “Tall Tales” from the Old Timer. Earl spent most of his life in Carlin, served as Mayor, and passed on at the ripe age of 99. All spelling and grammatical anomalies are the product of the author and he requested they not be changed.

Railroading, to me, was interesting, challenging and educating. This made the job seem worthwhile to me. It didn’t matter whether Id get rich or even make a decent living. What mattered to me was liking my job and wanting, no, looking forward to going to the job each day. That was the one little bit of wisdom (if it was wisdom) that I passed to my children – make your life’s work something that you enjoy and not to be a drudge. You’ll find peace and contentment – like what you do for a living! I know there are lots of people who will not agree with me. There are lots of people who believe the money earned is the most important. BUT I still believe due to the fact one goes through this life only once, peace, contentment and happiness are the most important. Sure — a little money to pay the bills is important too, it even make misery more comfortable BUT it can’t make you happy.

If I would have stayed on the farm I would have gotten killed by some accident or some angry farmer or rancher would have killed this dumb child for one of my dumb stunts. I didn’t like the cows or farm animals in general – have you ever gone to feed the chickens and about the time you throw out a handful of wheat the chicken squawks and try’s to fly, causing dust and feathers until you cant breathe. Or a dumb cow gets excited and runs smack into a barbwire fence. I never liked putting up the hay in the summer, nor did I like to feed hay to the stock in the winter.

I sure didn’t like working in the hospital – it made me too sick too often. I liked working on the road construction business nut it was too seasonal and so I ended up working for the railroad.

Railroading seemed to suit me. I liked the challenge. We worked by the rules. The rule book was near at hand at all times. Times seemed to be most important. One had to check his watch with the standard clock at the terminal when beginning the shift or trip, then compare time with the conductor, engineer and the rest of the crew. Accurate time was necessary and everyone had a regulation railroad watch. It had to be a 21 jewel pocket variety watch, not a wrist watch. It had to be inspected by a qualified watch inspector each month noted on your watch card and it had to be cleaned once a year. Every crew members watch had to indicate the same exact time or at least within a few seconds, no more than ten or fifteen seconds. Train schedules indicated by time tables that we all carried, informed everyone the time and place of every scheduled train. Passenger trains and hotshots had to be cleared by less important trains. All trains war controlled by train orders which told the crew of one train the time of scheduled trains (it late or on time) and where (what siding or yard track) to clear a certain train. Block signals controlled movement but time was a ruling factor. Time – speed – distance – all were important, but time was the one thing that made the railroad function.

Toward the end of my career, the railroad changed considerably. Diesel engines, giant box cars – instead of steam engines and thirty six foot box cars – Timken bearing wheels instead of friction bearings, miles and miles of ribbon rail instead of short lengths, automatic trail control – the dispatcher, hundreds of miles away, controls the block signals and believe it or not, by push button, controls the switches and can put one train in a siding to let another by. BUT to this day, long after retirement, I still look at my watch every little while and I know that other retirees do the same – habit.

I must tell about George Goodale and his watch. A day come that George had a little emergency in his financial situation and so he hocked his watch. (And I thought I was the only dumb one!) George came to work sans watch. All he had was the watch chain tied to his overalls and the end of the chain sticking into his watch pocket. It was a long time until payday so he had to work under these conditions for several days. He was really clever about it. It was at least two day before I had figured it out. Hed pull out the chain from the watch pocket in such a way that that no one ever saw the end of the chain. Then holding the end of the chain in the palm of his hand, as one would ordinarily hold his watch, he’d shield it – not obviously – just casually and ask the time – like he was comparing time. Then to top it off, he’d say, “That’s what my watch shows”.

Shortly before George got his watch back, the trainmaster stopped us and asked to check our watches. The engineer and fireman climbed down out of the engine and war first to compare time. I was next and I was about sick to think that would happen to George. SURPRISE!! When in doubt, punt. Out of the clear blue sky, George said, “What time did you say you have?” The trainmaster looked at his watch, counting seconds, then told George the time. George, still shielding the end of his watch chain, replied, “That’s just what my watch says, I’m really five seconds off.” He calmly put the chain back into his watch pocket and walked away. The trainmaster didn’t suspect a thing.